Conversations around the Water Table with Project Blue Thumb (Part Four)

Active reconciliation

By Amy Spark

This post is part four of a six-part interview series conducted and written by Project Blue Thumb.

Project Blue Thumb is a multi-stakeholder social lab co-convened by the Red Deer River Watershed Alliance and Alberta Ecotrust Foundation that takes a whole system approach to protecting water quality in the Red Deer River watershed. Building on the work of our current members, the PBT organizing team reached out to 13 multi-sector practitioners to hear their thoughts about the future of water in Alberta and potential directions. This post provides a snapshot from several interviews relating to water issues and reconciliation.

From the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada to the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, the past few years have seen communities across Canada grapple with the idea of reconciliation. It’s a conversation that is essential for the water community to engage in.

What does it mean to live in a watershed located on the traditional lands of Indigenous peoples? In what way should non-Indigenous groups be working toward water justice for Indigenous communities? These are questions without simple answers, questions that invite exploration and humility.

Project Blue Thumb participants think a lot about reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples as neighbours living and working in the watershed. We’ve also talked in a different way about reconciling watershed activities for the people living within it and downstream through a worldview that protects water and watershed function. These are daunting tasks, and like most journeys of reconciliation, it hasn’t always been smooth or easy.

Reconciliation is complex, and part of what makes this path so complex is the difficulty in seeing the bias behind our worldview.

So much of how we see the world is taken for granted, and we may not often stop to consider how our perspective and culture influences our actions and beliefs. However, we’ve been fortunate to meet with First Nations leaders and community members who are patient, knowledgeable, and honest. They are helping us navigate the often uncertain and emotional journey of reconciliation.

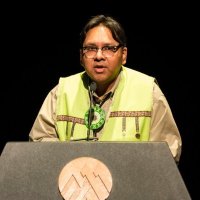

One of these leaders is Bill Snow, a member of the Stoney Tribal Administration. Chatting with Bill is akin to reading a history book and Twitter feed at the same time: getting caught up to date on current events while simultaneously learning irrigation history from the 1930s. Here is a snapshot from our conversation with him.

* * *

PBT: Can you provide some commentary on Alberta’s water system especially as it pertains to the Stoney Nakoda?

Bill: Water rights have caused a great deal of conflict over the years. The Northwest Irrigation Act of 1894 did not apply to reserves, so this early legislation excluded First Nations people. Because of this, the Plains First Nations had to find a way to develop irrigation agreements with the federal government, while the Stoney had hydro agreements since our area is more mountainous. Due to these technological developments, it means our water rights are very different than everyone else’s. Since then, there has been a gap between water resources and First Nations people.

PBT: What is the significance of water for you and your community?

Bill: There is a cultural aspect to water. It’s used for ceremonial purposes, and impacts everything that we do. If there’s no water quality, then there’s no hunting or gathering rights.

PBT: What is the relationship between traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) and western science in regards to water in Alberta?

Bill: We arrive at the same decision but through different ways. Take gravel pits for example. We are saying the same thing: we need to leave gravel pits alone, and we can’t be developing right up to the edge of a water body. It’s just asking for trouble. But even though we are saying the same thing, we’re saying them for different reasons. We (the Stoney) are saying it for cultural reasons, not just strictly scientific or ecological ones. What we have been asking [through SSRP] is to have cultural monitoring as part of research work. Embedding TEK in existing research models is a piece that’s really missing.

PBT: You mentioned the cultural significance of water. When you say more cultural awareness is needed, what do you mean?

Bill: Cultural awareness means understanding First Nations history and cultural teachings – how we regard water, how we manage wildlife, etcetera – and understanding that a lot of that was taken away through oppression. It means understanding that we still don’t have access to certain landscapes.

We have to understand we are part of a system that’s already existing… When the time comes, the river is going to go wherever it wants to go. We need to act like we are part of the larger system. The price of oil or wood should not be the only consideration when development starts. It should be the cultural aspect of land, because that’s been totally disregarded.

Bill Snow, Stoney Tribal Administration

* * *

The Treaty 7 Water Sub-table, a working group of the South Saskatchewan Regional Plan (SSRP), invited Project Blue Thumb representatives to attend their biannual meeting in April. Formed in 2010, this Sub-table is a forum for Treaty 7 First Nations, Alberta Environment, and Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada “to discuss overarching water issues, shared priorities, best practices, policy matters, and possible areas of alignment” (PFSRB 2014). We were honoured by the invitation, and to learn firsthand about the water priorities of local First Nations.

Our understanding of the cultural aspect of water mentioned by Bill was enriched at this meeting. Several elders described the quality of water in regards to whether one could drink from it and swim in it. For them, water quality is less about western science parameters and numbers, and more about how we interact with water, what it can teach us, and the connections it brings us. In the powerful words of Mike Oka of Blood Tribe, “water is a great medicine”.

There are multiple ways to ‘measure’ water quality, and our worldview strongly influences our understanding of this quality.

Some may view water quality as the ability to enjoy it with their families. Some view water quality in relation to Treaty rights. Others perceive it as the level of contaminants or water pH (acidity). Still others may assess water quality by its taste or colour. For some, it is even more complex than this. Michelle Daigle, Research Fellow at the University of British Columbia and member of the Constance Lake First Nation in Ontario, explains that the river is kin (Daigle 2017). The river is their grandmother. Therefore, water is seen as an independent lawful actor. In addition, Cree law is practiced through the use of river water. So ‘water quality’ has numerous implications for her Nation: legal, spiritual, and familial.

These various understandings of quality have implications for the work of Project Blue Thumb, as our mission is to improve water quality in the Red Deer River watershed. It’s clear that the simple concept of ‘water quality’ can be interpreted in multiple ways. This highlights the unique opportunities and challenges of reconciliation.

There is one strongly held view on water quality that most seem to agree on in Alberta: ensuring our water is protected at the source.

Source water protection plans at the regional, municipal, and reserve level are now priorities for governments and users. Examples include EPCOR’s Watershed Protection Program for the North Saskatchewan River region and the City of Calgary source water protection plan, a draft of which is slated to be released December 2017. Siksika Nation is the first in the Treaty 7 region with a source water protection plan, funded by Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada through the First Nations Technical Services Advisory Group (TSAG). Siksika is now looking for additional funds to further implement this plan. Many First Nations in Treaty 6, 7, and 8 have developed or are currently developing Source Water Protection Plans. Protecting water at the source is clearly a priority that demands attention by multiple groups.

Not only does it demand attention by multiple groups, it’s an issue which requires collaboration. Approaching projects through a reconciliation lens, such as source water protection, has the potential to bring Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities together. Yet, it requires trust, strong relationships, and common values. These aren’t easily formed, but as we’re learning at Project Blue Thumb, there are ways to begin deepening trust and relationships.

Part of reconciliation is working on truly collaborative projects. Projects that go beyond merely inviting someone else to your meetings or initiatives. Sometimes we need to approach our Indigenous neighbours and ask, ‘How can we help you protect water?’ It’s about getting to know one another and using ideas, frameworks, and worldviews from both perspectives. We are hopeful and keen to put reconciliation into action in the Red Deer River watershed.

Check out our next installment of Conversations around the Water Table scheduled to be published on June 20, 2017. Keith Ryder and Mary-Ellen Tyler will explore the effect urbanization is having on rural communities, and the role municipalities play in designing our water futures…

Curious about the project? See the Project Blue Thumb blog for information on our interview series, or join in the conversation on Twitter: @BlueThumbLab #ABwater.

Sources:

Daigle, M. 2017. Embodying our Kinship Responsibilities in and through Water. 37th Annual Community Forum presented by the Calgary Institute for the Humanities and the Faculty of Arts at the University of Calgary: Water in the West, 12 May, Calgary.

Partners FOR the Saskatchewan River Basin. 2014. First Nations Water Initiative: The State of the Saskatchewan River Basin. Saskatoon: PFSRB.