“What’s in your water?” event press release

Busting the myths and concerns about what’s in our water: Alberta organizations team-up to improve public information on water quality in the Bow River Basin

CALGARY, ALBERTA, Jan. 19, 2018 – How concerned should I really be about the fluoride in my drinking water? Why is water quality such an issue in many Indigenous communities? Do I need to worry about lead in my pipes? What is the level of harmful chemicals in my local river and is it safe to swim and fish? These, among others, are questions the public grapples with when thinking about the water they drink and enjoy, and which supports Alberta’s aquatic ecosystems.

Come explore what’s in your water!

Join the Alberta WaterPortal at one of three interactive exhibits with games and activities about water quality in the Bow River. Test your knowledge of water misconceptions, learn about water treatment in your communities, and try out water testing to learn about what’s impacting your water.

Family friendly and complimentary food and drinks will be available.

Three exhibit dates and venues:

- Calgary event, January 25th at the Alberta Wilderness Association

- Canmore event, February 1st at Elevation Place

- Strathmore event, February 8th at the Strathmore Civic Centre

To sign up for the free event visit the Eventbrite page here.

Stop by anytime between 5:30pm and 8:30pm for some fun activities for all ages.

For inquires please contact the Alberta WaterPortal

These events are made possible through the partnership and generous support of:

Insights from “The Water-Energy-Food Nexus: Which way? Right way?” Workshop

By Therese Baluyot

On July 31, the Alberta WaterPortal held a workshop entitled “The Water-Energy-Food Nexus: Which way? Right way?”. The workshop brought together stakeholders from academia, water management, food, energy and other sectors to stimulate the engagement and discussion on how to educate and inform Albertans about the Water-Energy-Food Nexus (the “Nexus”). The Nexus is the intricate link between producing enough food, meeting growing energy needs, and ensuring there is sufficient water for people. In recent years, the Nexus concept has been acknowledged in the domain of environmental science and natural resource governance. It has become the defining term for understanding the interconnections between water, energy, and food. [1] The anticipated outcome of the workshop was to gather ideas and feedback for the development and application of the Nexus concept in Alberta.

The workshop was structured around the following activities:

Draw The Nexus – Participants were provided with poster boards, markers, and printed graphic materials to create a system map of their conceptualization of the Nexus. A representative from each table presented their Nexus system map and how their team understood it.

Conversations around the Water Table with Project Blue Thumb (Part Six)

Reflections on Water for Life

By Amy Spark

This post is the final installment of a six-part interview series conducted and written by Project Blue Thumb.

Project Blue Thumb is a multi-stakeholder social lab co-convened by the Red Deer River Watershed Alliance and Alberta Ecotrust Foundation that takes a whole system approach to protecting water quality in the Red Deer River watershed. Building on the work of our current members, the PBT organizing team reached out to 13 multi-sector practitioners to hear their thoughts about the future of water in Alberta and potential directions. This post provides a snapshot from a few of our interviews relating to the Water for Life strategy.

Let’s take a trip down memory lane to 2003. It was a big year for water in Canada, especially along our three coasts: the largest ice shelf in the Artic fractured, hurricane Juan terrorized Halifax, and Canada’s first Marine Protected Area was declared off the coast of B.C. But what was happening in Alberta far away from these saltwater events? The provincial Water for Life (WFL) strategy was introduced by Alberta Environment. It may not have made national headlines to the same degree, but for those working in the water world of Alberta, it was a first of its kind.

The Water for Life strategy was designed to balance water quality and quantity needs with environmental concerns. The overarching goals of the framework incorporate social, economic, and environmental aspects of water issues:

1. Safe, secure drinking water supply

2. Healthy aquatic ecosystems

3. Reliable, quality water supplies for a sustainable economy

(Alberta Environment 2003, p.7)

Flood. Rinse. Repeat: The costly cycle that must end

By Glenn McGillivray

This piece was originally published in The Globe and Mail on 7 May 2017.

Once again, homes located alongside a Canadian river have flooded, affected homeowners are shocked, the local government is wringing its hands, the respective provincial government is ramping up to provide taxpayer-funded disaster assistance and the feds are deploying the Armed Forces.

In Canada, it is the plot of the movie Groundhog Day, or the definition of insanity attributed to Albert Einstein: Doing the same thing over and over again and expecting a different result.

At least in the movie, Bill Murray’s character learns from his mistakes. This can’t seem to be said of how we manage flood in this country.

In recent years, we have seen the cycle played out in such places as the Richelieu Valley after the spring 2011 flooding, and southern Alberta after the June 2013 deluge.

First, a homeowner locates next to the river, oftentimes because of the view (meaning a personal choice is being made). Many of these homes are of high value.

Then the snow melts, the ice jams or the rain falls and the flood comes. Often, as is the case now, the rain is characterized by the media as being incredible, far outside the norm. Then a scientific or engineering analysis later shows that what happened was not very exceptional.

These events are not caused by the rain, they are caused by poor land-use decisions, among other public-policy foibles. This is what is meant when some say there are no such things as natural catastrophes, only man-made disasters.

Finally, the province steps in with disaster assistance then seeks reimbursement from the federal government through the Disaster Financial Assistance Arrangements. In any case, whether provincial or federal, taxpayers are left holding the bag.

In some instances, attempts are made to prevent or lessen the risk of a recurrence through the construction of mitigation infrastructure, like dams, levees, bypasses and the like. These can have the unintended and surprising result of angering property owners (many homeowners in High River, Alta. were upset when a three-metre berm constructed after the June 2013 flood “ruined their view”).

In some cases, property buyouts for high-risk homes are offered. Back in the day, after Hurricane Hazel ravaged parts of Southern Ontario, killing more than 80 people, homeowners on flood plains were bought out at fair market value and their neighbourhoods were converted into parkland. Today, these parks flood from time to time, but no private property is damaged and no one dies. The program is still viewed as a best practice in how to run a mandatory flood buyout program.

The voluntary buyouts offered by the Alberta government after the 2013 event, conversely, are viewed by many as a failure. Only 94 homeowners of a possible 254 accepted the offer.

With all this being said, buyout/relocation programs are a rarity. We normally just put things back the way they were and hope that the event never happens again. But just as the boreal forest is “designed to burn,” rivers are designed to flood; it’s what they do.

Sometimes the powers that be give us the chance not to repeat the mistakes from the past, but we seldom take them up on the offer, then it’s deja vu all over again.

So what is the root of the problem? Though complex problems have complex causes and complex solutions, one of the causes is that the party making the initial decision to allow construction (usually the local government) is not the party left holding the bag when the flood comes.

Just as homeowners have skin in the game through insurance deductibles and other measures, local governments need a financial disincentive to act in a risky manner. At present, municipalities face far more upside risk than downside risk when it comes to approving building in high-risk hazard zones. When the bailout comes from elsewhere, there is no incentive to make the right decision – the lure of an increased tax base and the desire not to anger local voters is all too great.

Reducing natural disaster losses in Canada means breaking the cycle – taking a link out of the chain of events that leads to losses.

Local governments eager for growth and the tax revenue that goes with it need to hold some significant portion of the downside risk in order to give them pause for thought. Enough, at least, so they may think twice about making risky decisions that put people and property directly at risk.

To borrow the title of another movie, something’s gotta give.

Glenn is the Managing Director, Institute for Catastrophic Loss Reduction.

Conversations around the Water Table with Project Blue Thumb (Part Five)

Municipalities

by Amy Spark

This post is part five of a six-part interview series conducted and written by Project Blue Thumb.

Project Blue Thumb is a multi-stakeholder social lab co-convened by the Red Deer River Watershed Alliance and Alberta Ecotrust Foundation that takes a whole system approach to protecting water quality in the Red Deer River watershed. Building on the work of our current members, the PBT organizing team reached out to 13 multi-sector practitioners to hear their thoughts about the future of water in Alberta and potential directions. This post provides a snapshot from a few of our interviews relating to the role of municipalities in the water system.

My morning walk to work along the Bow River epitomizes the dual nature of cities. On my right, geese honk, beavers chew, and ice jams ebb and flow. To my left, rush hour traffic speeds by and the Calgary LRT glides along the Blue Line. Cyclists and runners whiz by in both directions. I’m caught in the beautiful crossfire of nature-in-the-city and city-in-the-watershed.

Cities have a storied reputation. They have been described as thriving ecosystems1, sanctuaries2, and hubs of innovation3,4. However, they are also the cause of much of our environmental distress due to high populations and strained infrastructure. Large municipal centres rely on significant amounts of water from rivers, make significant land-use decisions, and impact downstream waters through nutrients, sediment, and even pharmaceuticals5,6. Yet cities also house universities, research labs, non-profits, and others thinking about these problems and striving for solutions. They are simultaneously sources of tradition and innovation; deterioration and opportunity.

Conversations around the Water Table with Project Blue Thumb (Part Four)

Active reconciliation

By Amy Spark

This post is part four of a six-part interview series conducted and written by Project Blue Thumb.

Project Blue Thumb is a multi-stakeholder social lab co-convened by the Red Deer River Watershed Alliance and Alberta Ecotrust Foundation that takes a whole system approach to protecting water quality in the Red Deer River watershed. Building on the work of our current members, the PBT organizing team reached out to 13 multi-sector practitioners to hear their thoughts about the future of water in Alberta and potential directions. This post provides a snapshot from several interviews relating to water issues and reconciliation.

From the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada to the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, the past few years have seen communities across Canada grapple with the idea of reconciliation. It’s a conversation that is essential for the water community to engage in.

What does it mean to live in a watershed located on the traditional lands of Indigenous peoples? In what way should non-Indigenous groups be working toward water justice for Indigenous communities? These are questions without simple answers, questions that invite exploration and humility.

Project Blue Thumb participants think a lot about reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples as neighbours living and working in the watershed. We’ve also talked in a different way about reconciling watershed activities for the people living within it and downstream through a worldview that protects water and watershed function. These are daunting tasks, and like most journeys of reconciliation, it hasn’t always been smooth or easy.

Reconciliation is complex, and part of what makes this path so complex is the difficulty in seeing the bias behind our worldview.

So much of how we see the world is taken for granted, and we may not often stop to consider how our perspective and culture influences our actions and beliefs. However, we’ve been fortunate to meet with First Nations leaders and community members who are patient, knowledgeable, and honest. They are helping us navigate the often uncertain and emotional journey of reconciliation.

One of these leaders is Bill Snow, a member of the Stoney Tribal Administration. Chatting with Bill is akin to reading a history book and Twitter feed at the same time: getting caught up to date on current events while simultaneously learning irrigation history from the 1930s. Here is a snapshot from our conversation with him.

* * *

PBT: Can you provide some commentary on Alberta’s water system especially as it pertains to the Stoney Nakoda?

Bill: Water rights have caused a great deal of conflict over the years. The Northwest Irrigation Act of 1894 did not apply to reserves, so this early legislation excluded First Nations people. Because of this, the Plains First Nations had to find a way to develop irrigation agreements with the federal government, while the Stoney had hydro agreements since our area is more mountainous. Due to these technological developments, it means our water rights are very different than everyone else’s. Since then, there has been a gap between water resources and First Nations people.

PBT: What is the significance of water for you and your community?

Bill: There is a cultural aspect to water. It’s used for ceremonial purposes, and impacts everything that we do. If there’s no water quality, then there’s no hunting or gathering rights.

PBT: What is the relationship between traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) and western science in regards to water in Alberta?

Bill: We arrive at the same decision but through different ways. Take gravel pits for example. We are saying the same thing: we need to leave gravel pits alone, and we can’t be developing right up to the edge of a water body. It’s just asking for trouble. But even though we are saying the same thing, we’re saying them for different reasons. We (the Stoney) are saying it for cultural reasons, not just strictly scientific or ecological ones. What we have been asking [through SSRP] is to have cultural monitoring as part of research work. Embedding TEK in existing research models is a piece that’s really missing.

PBT: You mentioned the cultural significance of water. When you say more cultural awareness is needed, what do you mean?

Bill: Cultural awareness means understanding First Nations history and cultural teachings – how we regard water, how we manage wildlife, etcetera – and understanding that a lot of that was taken away through oppression. It means understanding that we still don’t have access to certain landscapes.

We have to understand we are part of a system that’s already existing… When the time comes, the river is going to go wherever it wants to go. We need to act like we are part of the larger system. The price of oil or wood should not be the only consideration when development starts. It should be the cultural aspect of land, because that’s been totally disregarded.

Bill Snow, Stoney Tribal Administration

* * *

The Treaty 7 Water Sub-table, a working group of the South Saskatchewan Regional Plan (SSRP), invited Project Blue Thumb representatives to attend their biannual meeting in April. Formed in 2010, this Sub-table is a forum for Treaty 7 First Nations, Alberta Environment, and Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada “to discuss overarching water issues, shared priorities, best practices, policy matters, and possible areas of alignment” (PFSRB 2014). We were honoured by the invitation, and to learn firsthand about the water priorities of local First Nations.

Our understanding of the cultural aspect of water mentioned by Bill was enriched at this meeting. Several elders described the quality of water in regards to whether one could drink from it and swim in it. For them, water quality is less about western science parameters and numbers, and more about how we interact with water, what it can teach us, and the connections it brings us. In the powerful words of Mike Oka of Blood Tribe, “water is a great medicine”.

There are multiple ways to ‘measure’ water quality, and our worldview strongly influences our understanding of this quality.

Some may view water quality as the ability to enjoy it with their families. Some view water quality in relation to Treaty rights. Others perceive it as the level of contaminants or water pH (acidity). Still others may assess water quality by its taste or colour. For some, it is even more complex than this. Michelle Daigle, Research Fellow at the University of British Columbia and member of the Constance Lake First Nation in Ontario, explains that the river is kin (Daigle 2017). The river is their grandmother. Therefore, water is seen as an independent lawful actor. In addition, Cree law is practiced through the use of river water. So ‘water quality’ has numerous implications for her Nation: legal, spiritual, and familial.

These various understandings of quality have implications for the work of Project Blue Thumb, as our mission is to improve water quality in the Red Deer River watershed. It’s clear that the simple concept of ‘water quality’ can be interpreted in multiple ways. This highlights the unique opportunities and challenges of reconciliation.

There is one strongly held view on water quality that most seem to agree on in Alberta: ensuring our water is protected at the source.

Source water protection plans at the regional, municipal, and reserve level are now priorities for governments and users. Examples include EPCOR’s Watershed Protection Program for the North Saskatchewan River region and the City of Calgary source water protection plan, a draft of which is slated to be released December 2017. Siksika Nation is the first in the Treaty 7 region with a source water protection plan, funded by Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada through the First Nations Technical Services Advisory Group (TSAG). Siksika is now looking for additional funds to further implement this plan. Many First Nations in Treaty 6, 7, and 8 have developed or are currently developing Source Water Protection Plans. Protecting water at the source is clearly a priority that demands attention by multiple groups.

Not only does it demand attention by multiple groups, it’s an issue which requires collaboration. Approaching projects through a reconciliation lens, such as source water protection, has the potential to bring Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities together. Yet, it requires trust, strong relationships, and common values. These aren’t easily formed, but as we’re learning at Project Blue Thumb, there are ways to begin deepening trust and relationships.

Part of reconciliation is working on truly collaborative projects. Projects that go beyond merely inviting someone else to your meetings or initiatives. Sometimes we need to approach our Indigenous neighbours and ask, ‘How can we help you protect water?’ It’s about getting to know one another and using ideas, frameworks, and worldviews from both perspectives. We are hopeful and keen to put reconciliation into action in the Red Deer River watershed.

Check out our next installment of Conversations around the Water Table scheduled to be published on June 20, 2017. Keith Ryder and Mary-Ellen Tyler will explore the effect urbanization is having on rural communities, and the role municipalities play in designing our water futures…

Curious about the project? See the Project Blue Thumb blog for information on our interview series, or join in the conversation on Twitter: @BlueThumbLab #ABwater.

Sources:

Daigle, M. 2017. Embodying our Kinship Responsibilities in and through Water. 37th Annual Community Forum presented by the Calgary Institute for the Humanities and the Faculty of Arts at the University of Calgary: Water in the West, 12 May, Calgary.

Partners FOR the Saskatchewan River Basin. 2014. First Nations Water Initiative: The State of the Saskatchewan River Basin. Saskatoon: PFSRB.

Lessons I have learned experiencing floods in Canada and the Philippines

By Therese Baluyot

May to July is usually when we receive the heaviest rainfall in Calgary, which can cause flooding. One recent flood in the minds of Canadians was the devastating flood in southern Alberta in 2013. Over 48 hours, 68mm of rain fell when a storm stopped over Calgary on June 19. [1]

Growing up in the Philippines, I am also no stranger to torrential rains and floods. Typhoons can hit the Philippines at any time of the year. According to 2013 article from Time Magazine, the Philippines is “the most exposed country in the world to tropical storms”. [2]

Both countries where I experienced flooding have many stories of loss and destruction, but there are also lessons for the future. Four lessons I learned:

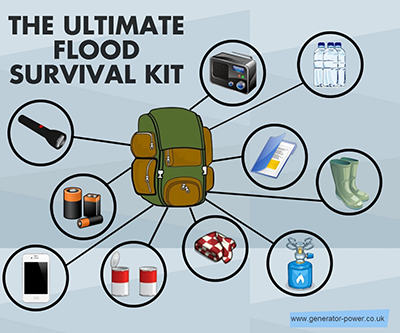

1. Preparedness is a must

Although it is good to learn from disasters, it is important to learn before these disasters even happen. By practicing for disasters, you are accepting the fact that it can affect you, but you are also proving to yourself that when it does come, you will be ready. There is no need to wait until the disaster arrives before you start evaluating your emergency plans. Check out this intensive guide on flood preparedness [3] before and after a flood so you can be prepared.

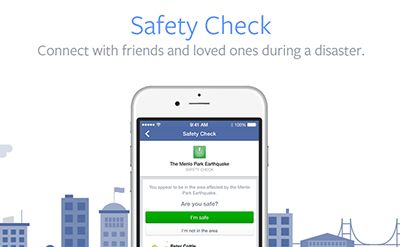

2. Communication is everything

Anything can happen at any given time. Stay up to date with news advisories regarding water and weather conditions. Being informed is the first step with planning ahead. Here are some key websites you should check before you go out. [4] Social media is also a great tool for communication. Facebook has a Safety Check function that allows people to quickly share that they are safe with friends and family. [5] Twitter is also a great social media tool to use during times of crisis and emergencies because it is live, open and public. You can also use the hashtag feature to track and monitor information and easily find updates. [6]

3. Help one another but take care of yourself first

The 2013 Alberta floods further demonstrated just how important mutual assistance between local communities and government is in aiding those affected by the disaster. Civilian assistance came naturally and people came together to help one another. Although volunteering is a great way to give back to the community and ease the workload of our first respondents, we should take care of ourselves first before helping others so we do not injure ourselves. Here are some great tips to ensure safety while volunteering. [7]

4. Always educate yourself about flooding and other water-related calamities

Being informed and educated is the first step in preparing for disasters. Even though I have experienced many water-related calamities in my life, I still have lots of things to learn. As this year’s summer intern, in less than a week, WaterPortal has opened my eyes to many interesting facts about water I did not know. Having only experienced flooding caused by heavy rainfall, one surprising fact I found was that there are three types of flooding. [8]

There are the four things I have learned as a flood survivor in the Philippines and in Canada. I hope you keep these lessons in mind this year and years to come. Stay safe!

Therese is an information design student at Mount Royal University. She came to Canada in 2011 from the Philippines. She loves her dog Felix and eats rice with everything. The Alberta WaterPortal is delighted to have her on board with us this summer!

Sources:

[1] Flood season: understand, be prepared and stay informed http://www.calgarycitynews.com/2017/05/flood-season-understand-be-prepared-and.html

[2] The Philippines is the most storm exposed country on earth http://world.time.com/2013/11/11/the-philippines-is-the-most-storm-exposed-country-on-earth/

[3] Flood Preparedness http://albertawater.com/stay-safe/emergency-preparedness/flood-preparedness

[4] Advisories and Warnings http://albertawater.com/stay-safe/advisories-and-warnings

[5] Facebook Safety Check https://www.facebook.com/help/695378390556779

[6] Twitter for crisis and disaster relief https://blog.twitter.com/2016/twitter-for-crisis-and-disaster-relief-in

[7] After a flood – Volunteering http://albertawater.com/stay-safe/emergency-preparedness/after-a-flood

[8] What is flooding? http://albertawater.com/what-is-flooding

Conversations around the Water Table with Project Blue Thumb (Part Three)

Water worth

By Amy Spark

This post is part three of a six-part interview series conducted and written by Project Blue Thumb.

Project Blue Thumb is a multi-stakeholder social lab co-convened by the Red Deer River Watershed Alliance and Alberta Ecotrust Foundation that takes a whole system approach to protecting water quality in the Red Deer River watershed. Building on the work of our current members, the PBT organizing team reached out to 13 multi-sector practitioners to hear their thoughts about the future of water in Alberta and potential directions. This post provides a snapshot from a few of our interviews relating to the multifaceted ways we value water.

I was reflecting recently on the value of a sticker. Remember what it felt like to receive a sticker on an assignment as a child? Remember what that meant: a symbolic pat on the back, something to be proud of. Even knowing their ‘true’ value as an adult (500 stickers for $4.99) still doesn’t take away the magic it represented.

A few weeks ago I was trying to determine the value of a postage stamp so I could calculate how many I needed on a letter to the UK. Rummaging through my desk drawer, I found some stamps that were too new to be valuable, and too old to be memorable. After peppering my letter with likely way too many stamps – just to be safe – I realized the ‘worth’ of them was just as symbolic as those stickers I received as a child. Although they are relatively cheap, they symbolize something very important to me: staying connected with my brother 6400 kilometres away.

The concept of ‘value’ has multiple dimensions. It is one of those queer English words which can act as both a verb and noun; one can value something and also espouse certain values. Values are inherently personal, yet the concept also governs all of our economic activities – seemingly one of the most impersonal activities we engage in.

This complexity is heightened when thinking of value in the context of water and the environment. It can take on the connotation of either intrinsic worth or monetary assessment.

Should we value water for the goods and services it provides to us, or for the endless impacts it has on our mental and physical health and the viability of ecosystems? At Project Blue Thumb, we often hear this discussion during workshops and interviews.

Let’s take a look at some perspectives we’ve heard over the past few weeks.

Laura Lynes with The Rockies Institute suggests that “we can’t have transformative change if we continue to look at everything with an anthropocentric view.” In fact, it is precisely this human-centered view which obscures the immense value nature holds.

“If we start to look at the value in this province… whether it is the river itself, fish, or animals (because we can also attribute value to other things that water supports) then all of a sudden water becomes such a greater need and value within our lives. We could start a different narrative around the value of water.”

By compartmentalizing the value of water, as opposed to looking at the value of the system to both humans and non-humans, Laura suggests we’re missing the larger picture.

Laura Lynes

In contrast, there is an argument for placing monetary value on water. It allows the vast benefits of water to be quantified – however imperfectly – so that groups can begin to express value in a common language: the language of economics. Vice Dean of Agricultural, Life, and Environmental Sciences at the University of Alberta, Dr. Vic Adamowicz explains, “Recognizing the value of environmental goods and services levels the playing field in the world of economics. If you don’t put a value on something it may effectively be valued at zero. Measuring a monetary value shows that environmental goods can have significant economic importance. It’s not about something being commoditized. It’s about valuation.”

This is precisely the objective of the burgeoning field of ecosystem services analysis: to place a value on the invaluable. These are the types of challenges academics and practitioners have begun to tackle, including the Natural Capital Lab here in Canada. The way Vic sees it, “We have designed markets around goods and services, so how can we support non-market items like source water while using a market economy?”

Dr. Vic Adamowicz

However, it seems Canadians are a bit divided when it comes to putting a price on water. According to a recent RBC Canadian Water Attitudes study, “Although seven in ten [Canadians] agree that people will waste water if there is no price put on it, about the same number say that the price of water is high enough to ensure it is treated as a valuable resource.” (2017, p.7). This disparate view highlights the complexity of water valuation.

As ecosystem services analysis is disseminated and used, further questions come to light. Brett Purdy, Senior Director with Alberta Innovates points out, “For the most part, water has been free. But now, if we start to put a price on water, what will this look like? Do we put a price on water that’s different between food, energy, and recreation? Which do we value more?”

Brett Purdy

Is all water-use treated equal? Where does the line of ‘necessary’ water end and ‘extra’ water begin? If we do begin to economize water in this province, there are many implications to be discussed. For example, where does the valuation end? Is it from only direct use, or indirect use?

From a WaterPortal blog post on March 21, 2017, Brie Nelson suggests wastewater should not only be valued by what can be extracted from it, but also by its potential as a resource. Is it possible to include all potential uses of water by a monetary assessment? Are we truly able to categorize and monetize the potential of our headwaters or groundwater? If the value of a postage stamp or children’s sticker is hard to quantify, water is even trickier.

Whether or not value is assigned, communicating that value can be difficult. Ecosystem service analyses are often used as a communication tool to impact policy and regulation decisions. However, intrinsic worth – the type of value Laura is emphasizing – is a lot harder to articulate. For example, the mental and physical health benefits of a local river for nearby residents are difficult to express via numbers. Instead stories, photographs, poetry, art, lived experience, and music can be a lot more rich and effective. In order to capture the ‘true’ value of water, I believe all are needed: the science, the social science, and the art.

The central question seems to be whether or not we want to include the environment as an economic factor in our market system.

By commoditizing water are we further distancing ourselves from our natural landscape, or valuing it enough to protect it? Essentially, do we want to change our behaviour by using tools and language we’re already familiar with (ie: the market system) or develop a new value sets and valuation methods? That’s for all of us, as citizens of a global community, to figure out.

I have a lot of fond memories of my family and water. We would take an annual trip to Adams Lake in Shuswap Country, where I would be thrown off the dock by the very brother I now stay connected with via snail mail. Although that lake has no direct economic effect on me, its existence is of value. I’m confident those living around the lake, and those who extract resources from it for their life and livelihood, value it as well – perhaps just using different language. In order to begin the conversation, it’s helpful to recognize that value is simultaneously economic, symbolic, and personal.

Check out our next installment of Conservations around the Water Table to be published 6 June, 2017 as we continue to explore the value of water through the topic of water rights and worldview. Bill Snow with the Stoney Tribal Administration will share his thoughts…

Curious about the project? See the Project Blue Thumb blog for information on our interview series, or join in the conversation on Twitter: @BlueThumbLab #ABwater.

Sources:

RBC Foundation Blue Water Project (2017). 2017 RBC Canadian Water Attitudes Study. Available at: http://www.rbc.com/community-sustainability/_assets-custom/pdf/CWAS-2017-report.pdf.

Conversations around the Water Table with Project Blue Thumb (Part Two)

New water paradigms

By Amy Spark and Josée Méthot

This post is part two of a six-part interview series conducted and written by Project Blue Thumb.

Project Blue Thumb is a multi-stakeholder social lab co-convened by the Red Deer River Watershed Alliance and Alberta Ecotrust Foundation that takes a whole system approach to protecting water quality in the Red Deer River watershed. Building on the work of our current members, the PBT organizing team reached out to 13 multi-sector practitioners to hear their thoughts about the future of water in Alberta and potential directions. This post provides a snapshot from a few of our interviews relating to reimagining water and the paradigms that guide us.

“Culture is like gravity: you do not experience it until you jump six feet into the air” – Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner

Conversations often veer off into unexpected and rewarding places. The latest round of Project Blue Thumb interviews found our team grappling with the fundamental patterns of thought that guide our water systems and management. These paradigms operate imperceptibly in the background of our day-to-day lives, guiding our thinking about how something should be done, made, or even thought about.

Here we present a few highlights from these interviews, with each person hinting or overtly calling for a type of paradigm shift. Dr. Nick Ashbolt is a municipal water researcher and professor at the University of Alberta School of Public Health. He is also working on an innovative Resource Recovery Centre northwest of Edmonton focusing on the next generation of community water services.

Shannon Frank is the Executive Director of the Oldman Watershed Council, currently working on a campaign to effectively engage recreationists in restoration projects in southern Alberta headwaters.